This one ran a little long, so I'm turning it into a two-parter. This part is about emacs and the theory of choosing your tools in general. In the next one, I'll show off a demo of how I use emacs to automate a task that is annoying toil but I don't do quite frequently enough to justify fully automating it.

In a previous post, I mentioned that half my job is moving big blobs of text around, and how important it is to automate that process. I'm going to provide a concrete example using my multi-tool of choice, emacs. Before I continue, of course, I should address the elephant in the room.

Why not vi?

I never really learned it.

That's not very satisfying

Yeah, sorry. Twenty years on from when I first encountered both tools in college, My use of emacs is pretty much just luck. I started learning it first, continued learning it, and now I have accreted a 103MB configuration directory that follows me around from computer to computer. If you tell me vi is great, I'll agree. If you tell me vi is better than emacs at something, I'll believe you.

But if you tell me there's something vi can do that emacs definitely cannot, I'll be modestly surprised and want to know more. Because that's the thing: these tools are more similar than different. And passionate arguments about which of two things that are 90% the same are better is a young person's game. In fact, on topics like this in general, as a word of advice:

For software of the same category, choose one and go deep on it. Know enough about its neighbors to learn more if you need to.

I find I cover more ground when I do this.

So why emacs?

What emacs offers that matters is the following:

Ancient

Emacs was written in 1976. It's older than MS-DOS and only three years younger than the XEROX Parc Alto, the first personal computer to offer a graphical user interface (at an affordable $32,000). Nothing in software is forever, but anything that has stuck around for 25 years in this industry has crocodile DNA. The reason this matters is that community matters for the longevity of software tools; if there's no community, you're building and maintaining it yourself, which is fine if that's your goal but a massive cost otherwise. If you're going to invest heavily in something, it should be something that probably won't fall out of fashion next week.

Degradable

Because of its age (and a community mentality of keeping it maximally compatible), emacs runs on UIs ranging from a full GUI to a decent-quality TTY emulator (i.e. command line). As a result, I rarely find a computing environment I can't bring up emacs on (with just a little configuration). It's comfortable to be able to quickly spin up a familiar development and editing environment on every machine I sit down at, and decreases friction from having to learn something novel.

Network-aware

I don't merely mean "can do TCP/IP" here. Emacs is constructed as a distributable tool; the editor engine and the client can be running in different programs and even on different machines. Furthermore, emacs is aware of SSH and can remote-control the filesystems of other machines, meaning I can edit remote files without having to spin up a shell on them or copy files back and forth. That proves to be a big deal pretty often in my modern ecosystem of remote controlling computers.

Deeply, deeply reconfigurable

This is the important property of the tool, the one that justifies keeping a 100MB config directory around and learning all the esoteric space-alien-language keyboard shortcuts and interface metaphors that predate such exotic topics as "mouse" and "desktop" (to say nothing of "cut", "copy" and "paste"). Emacs stands for Editor MACroS. There's a joke that emacs is really a virtual LISP machine that someone wrote a text editor in.

It's not a joke. It's the law and the whole of the law and it's magic.

Emacs lets you reconfigure basically everything. Every command, every menu option, every human activity is running a command that can be overridden. Even individual keystrokes are just bound to default "insert this character at the current point in the current buffer" functions. That massive extensibility means emacs is something more than a text editor: it's a development environment in which you can develop it. I've seen a full implementation of Tetris running in it. I'm in the process of writing a shell wrapper in it (more on that... Possibly never, I make no promises. ;) ).

|

| emacs is built on self-insert fictions |

And really, that's the most important thing. In fact, second word of advice:

Seek out the most powerful tools. The most powerful tools can modify themselves.

The tradeoff of doing such a thing is that you eventually end up with an emacs with one user. I don't expect anyone to understand or help me with my emacs configuration; there's 100MB of custom behavior on top of it. Hence, the need to go deep: to maintain a well-customized tool, you have to become an expert in it. if you really drill down on a tool, you may find that in the end, you're the only one who can fully understand what you've done to it.

|

| This is my editor, this is my GNU. I built it for me and not for you. |

What other tools do you use?

In my day-to-day, I have a handful of other things I develop with.

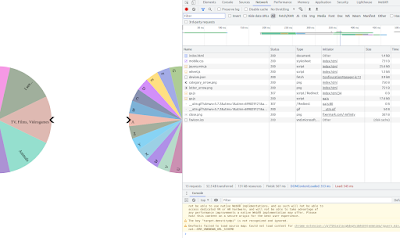

Chrome

This is a bit domain-specific, but: I use Chrome for my web development. Chrome has some overlap with emacs in terms of its extensibility, and the developer tooling is pretty solid. I've even built a (shudder) debuggable build of Chromium. Once. For a very special reason.

... and yes, working at Google is a huge part of this choice. I have no strong opinion on Firefox vs. Chrome, other than the ugly market truth that if you're trying to provide a service to the most people, debugging your website on Chrome and Safari first will cover more people's usage environment faster than Firefox.

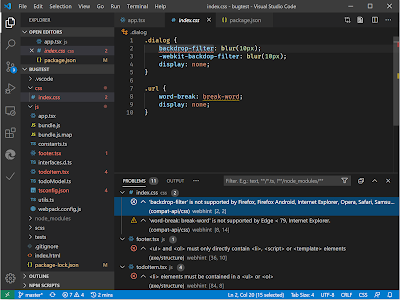

VSCode

It's weird that I use a second text editor, I know. But I've been pretty impressed with VSCode; for the kind of development I do (mostly TypeScript, JavaScript, and Java), it's a very effective IDE. The formatting, autocompletion, and static checking integration out of the box is simpler to configure than emacs (the one downside of a hyper-flexible editor: many ways to do a thing means many ways to do it wrong). And it shares emacs's comfort with operating in a networked environment, being able to connect to a remote instance of itself over SSH. It's possible that in 25 years, it'd be the kind of thing I'd recommend over emacs if it stands the test of time. I keep emacs launched in a second window for the few tasks VSCode makes harder (it can be very opinionated about auto-formatting files that already have a format set up that is incompatible with the VSCode defaults, and rather than either turning off the formatter or resetting its rules to match the ones in the target file, it's easier to just pop the file open in emacs and let its lack of auto-formatting help me out).

In my next post, I'll demonstrate a task I have to do not-infrequently and how I speed it up a bit with emacs.

No comments:

Post a Comment